- April 8, 2018

Art of fish

Stephen DiCerbo combines enthusiasm of fishing with creativity

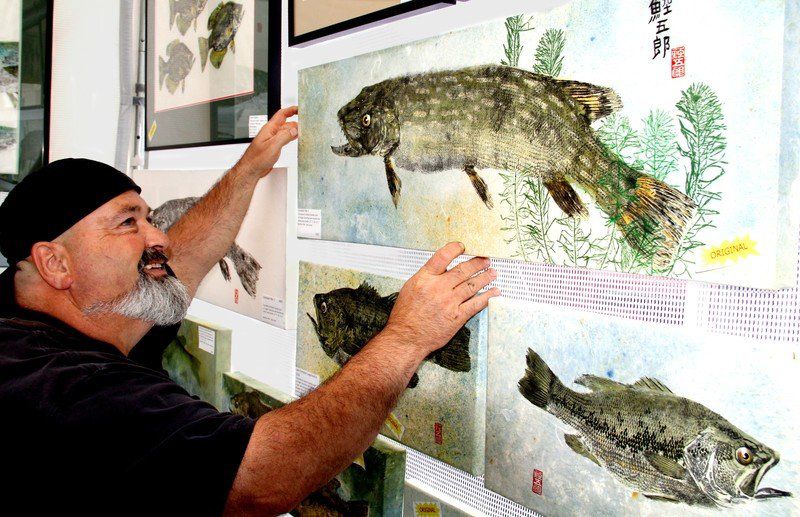

One generally doesn’t associate tossing a line in the water with creating unique works of art, but North Hudson’s Stephen DiCerbo has combined both of his passions into the Japanese art of gyotaku.

Literally meaning “fish rubbing,” gyotaku involves covering a fish with ink and then transferring the image to another surface, generally paper.

The artform was initiated more than 250 years ago and may have been utilized by fishermen to record their catches.

Similar techniques have been employed to create works of art that reproduce images of other natural objects such as leaves and flowers. Many of the rubbings are done with black ink with color added later.

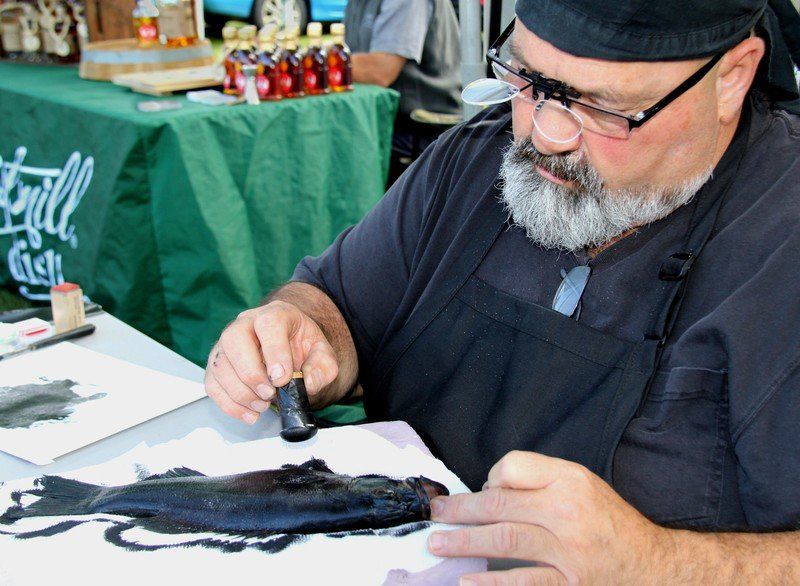

Watching DiCerbo work seems almost tedious at first as he methodically rubs a fish with black ink, which could be either an oil-based or water-soluble solution, making sure every scale and fin part is covered.

“I get better detail with oil, and put it on washi paper,” he stated.

Washi, which is often handmade, can be prepared from a variety of fibrous plants such as bamboo, hemp or wheat, and is stronger and less likely to tear than regular pulp-made paper. It is often used in other creative ways, such as origami as well as clothing, household items and even toys.

“Art and fishing have been parts of my life since I was 5 years old,” said DiCerbo, who does most of his fishing from Lake Champlain. “Several years ago, somewhere in my mind, I thought there was a process that could combine both. I got information from an out-of-print fishing encyclopedia.

“Later I joined the Nature Printing Society, and started hanging out with members of the NPS.”

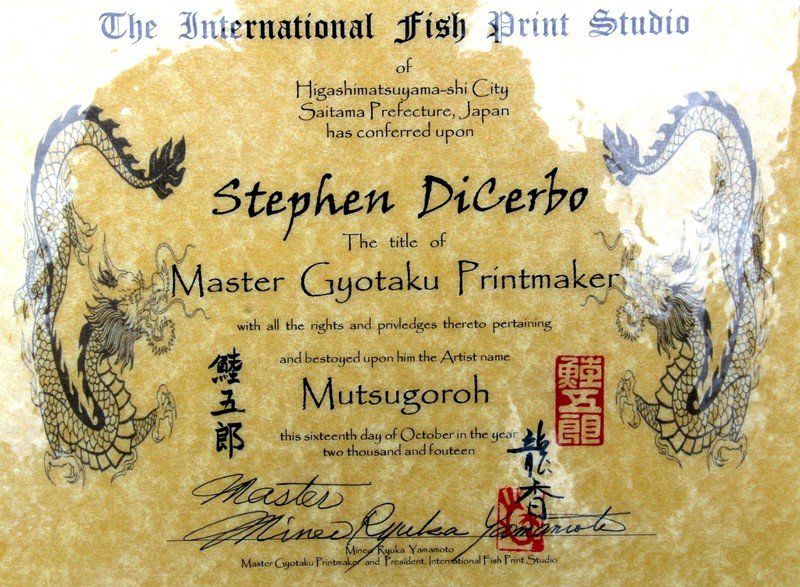

Proudly pointing to a certificate from the International Fish Print Studio of Higashimatsuyama City, Japan, DiCerbo noted that he has been conferred as a Master Gyotaku Printmaker and was given the artist name of Mutsugoroh.

“So basically, according to this, I am a mud skipper,” DiCerbo chuckled.

Email Alvin Reiner: rondackrambler@gmail.com

MORE INFO

Stephen DiCerbo’s work may be seen at several venues, and at times he conducts workshops. He can be contacted at www.facebook.com/stormtreestudio or by email at Stephen@stormtreestudio.com.

Japanese fish printing

Local artist gives workshops in Gyotaku printmaking

by Mikaela Foster May 20, 2016 12:00 PM

Stephen DiCerbo (“Master Mutsugoroh”) creates an indirect print portrait of a salmon. DiCerbo teaches the art of Gyotaku- Japanese fish printing.

NORTH HUDSON — Instead of taking the catch of the day to a taxidermist, anglers can learn the art of Japanese fish printing and immortalize a fish with ink on paper or fabric.

Local artist (and angler) Stephen Dicerbo of Stormtree Studio, also known as Master Mutsugoroh, teaches the art of gyotaku, or Japanese fish printing.

The art form involves using a real fish to make ink printed images. With his “interests at heart” being wildlife, art and illustration, gyotaku combines the artist’s passion for art and fishing.

This practice, Dicerbo said, dates back to 1860 in Japan and was not originally intended to be art.

Roughly translated, the artist said gyotaku means “fish stone rubbing” and was a way for a fisherman to record and prove his catch. Over the years, it evolved into an art form, which then branched off into two styles: direct and indirect.

The difference is in the ink application.

The art of Gyotaku- Japanese fish printing.

With the direct style, the ink goes directly on the fish to make a print and can be a quick process to make a large amount of prints.

For the indirect style, which works well for fine-scaled fish, material is adhered to the fish and the ink is applied to the material, capturing intricate details of the fish. This process, Dicerbo said, is “very meticulous” and is an “exercise in minimalism.”

“You can sit their for hours,” he said. “You can spend an entire day or two days on one image.”

Dicerbo said he has been an artist since he was a child, when he started drawing and never stopped. He earned and Associate of Science degree in Fish and Wildlife Technology in the 1980s, and years later, a Bachelor of Science in Science Illustration.

The artist also practices natural science illustration, fine art and printmaking and specializes in Ichthyologic subject matter.

Dicerbo has traveled to Japan and studied with a Master Gyotaku Printmaker, Sensai Yamamoto, with whom he studied with for over a decade before being “honored with the title of master” and receiving a Japanese artist’s name.

Mutsugoroh, his artist name, means “Japanese Blue Spotted Mudskipper,” which is his sensai’s favorite fish.

The artist will offer a workshop every month this summer, with the first one starting Memorial Day.

For more information, find Storm Tree Studio on Facebook.

May 20, 2016 12:00 PM

http://www.suncommunitynews.com/articles/the-sun/japanese-fish-printing/

By Jessica Bloch, BDN Staff •

Mitsuyoshi Yabe (left), a 23-year-old from Fukuoka, Japan, offers his critique as Bryce Carter, 13, of Fort Kent, tries his hand at creating a fish print during Kabe’s gyotaku demonstration Tuesday at the annual Guild of Natural Science Illustrators conference at the University of Maine at Fort Kent. Bryce’s parents, Heidi and Jason Carter, as well as other students, look on.

FORT KENT, Maine — A crowd gathered around Mitsuyoshi Yabe on Tuesday morning as he bent over a table in front of him and rubbed a piece of paper with his fingers.

He made one more pass with his fingers, and lifted up the piece of paper, holding it up to the 20 people around him. On the paper was a print of a fish. It was blurry and fuzzy, but the scales, tail, fins, eye socket and open mouth were easily identifiable.

The crowd cheered. Yabe didn’t say anything, but smiled and nodded his head. His demonstration of a Japanese fish printing technique called gyotaku had gone well.

Yabe’s presentation was part of the five-day Guild of Natural Science Illustrators annual conference, being held this year at the University of Maine at Fort Kent. More than 50 attendees from around the country and world, including some of the most renowned science illustrators in the field, are participating.

Yabe, 23, is an undergraduate student in a medical illustration program at Rochester Institute of Technology in New York.

Yabe communicates by using a notebook and pen he carries with him, encouraging people to write out questions or statements. He writes his responses in English.

On Tuesday, Yabe had some help from Stephen DiCerbo, a freelance illustrator from North Hudson, N.Y., who has been making gyotaku prints for 20 years. DiCerbo read aloud from the notebook whenever Yabe wanted to say something to the audience, and also provided some play-by-play as he watched Yabe create.

Gyotaku is a technique that came into use in the 1860s, DiCerbo said, and was originally used as a method of record-keeping and species identification. It evolved into a form of trophy art, similar to the practice of taxidermy, and finally into its current form as art technique. The basic method involves brushing ink or colored paint onto the fish, covering it with a piece of Japanese rice paper, and pressing down carefully to imprint the fish on the paper.

“For scientific illustrators who get into this, it’s just a looser style and you wind up having a lot of fun,” DiCerbo said. “It’s like finger painting for adults. And it’s really a variation on traditional printmaking methods. As you develop your technique you try to find ways to control the image so you get a finer piece of artwork at the end.”

Yabe’s technique is the one he learned as a teenager, when he was a fisherman in Japan.

“[Gyotaku is] so popular in Japan that if you go into fishing stores and the tackle stores, it’s all over the walls,” DiCerbo said, reading from statements Yabe wrote in his notebook. “He thinks it’s very beautiful and wonderful, and he’s still practicing and learning, like we all are.”

Thanks to Bryce Carter, a 13-year-old Fort Kent resident, Yabe had some fish with which to work. Carter caught two 5-inch yellow perch Monday evening in St. Froid Lake during a fishing outing with his family and brought them to the gyotaku demonstration Tuesday.

Yabe’s first step on Tuesday after wiping the perch was to pin the fish’s fins so they flared out from the body in preparation for the inking. He placed pieces of plastic foam under the tail and fins to stabilize the perch and used tweezers to poke out the fish’s eye, which would help create a white circle in the print. Some gyotaku artists paint in an eye on the print later in the process.

Yabe began to paint the perch with a small brush and dark India ink diluted with water — the traditional gyotaku ink is sumi, made of soot and water, but Yabe didn’t have any with him — from the head to the tail of the fish. Then, he used a clean paint brush in the opposite direction from which he had painted on the ink. This absorbs excess paint and allows the scales to show up more clearly in the print.

After inking the fish, Yabe covered it with a piece of the traditional rice paper, which is flexible and strong enough to withstand the next step. Yabe began to carefully rub the rice paper over the fish with his fingertip to coax the ink onto the paper.

Finally, Yabe peeled the paper from the fish with an image of the perch printed on the paper.

Carter had a chance to try gyotaku himself, and decided it was something he might work on at home.

“I thought this would be fun,” Carter said. “I like art, and I like to draw with pencil and paper.”

Dwight Gagnon, a conference attendee from Benton, watched part of the demonstration. He wasn’t sure he would include gyotaku in his work, but was interested to watch a technique he first saw in his student teaching days in Waterville.

“I wanted to see where it was, at this level,” said Gagnon, a 1976 UMFK graduate making his first trip to campus since his graduation. “In the labs, we’d take the fish, get a print, and the students would label the different anatomy features. I was fascinated to see what else was being done with it.”

The GNSI conference continues through Saturday. A juried exhibition of illustrators’ work will be on display this month at UMFK’s Acadian Archives

Fish art makes impression at Fort Kent conference